You are reading contentfolks—a fortnightly sporadic blend of sticky notes, big content ideas, and small practical examples. Thank you for being here! ~fio

Hey there 👋

If you’re human—which, these days, who knows?! 🤖—you surely, definitely, 100% experience the planning fallacy, a cognitive bias that makes you over-confident with your forecasts. Like me, you too are wired to ignore existing data points about how long something might take, and consistently underestimate future timelines:

Scientists and writers, for example, are notoriously prone to underestimate the time required to complete a project, even when they have considerable experience of past failures to live up to planned schedules.”1

Ha. If that sounded familiar, it’s because this fallacy shows up at work all the time—most notably, when we plan a new content or marketing deliverable. So let’s see if I can help: here are a couple of tried-and-tested methods that should help you overcome, or at least minimise, the planning fallacy and its (frustratiiinnnngggg) consequences.

Method one: start from the end 🔙

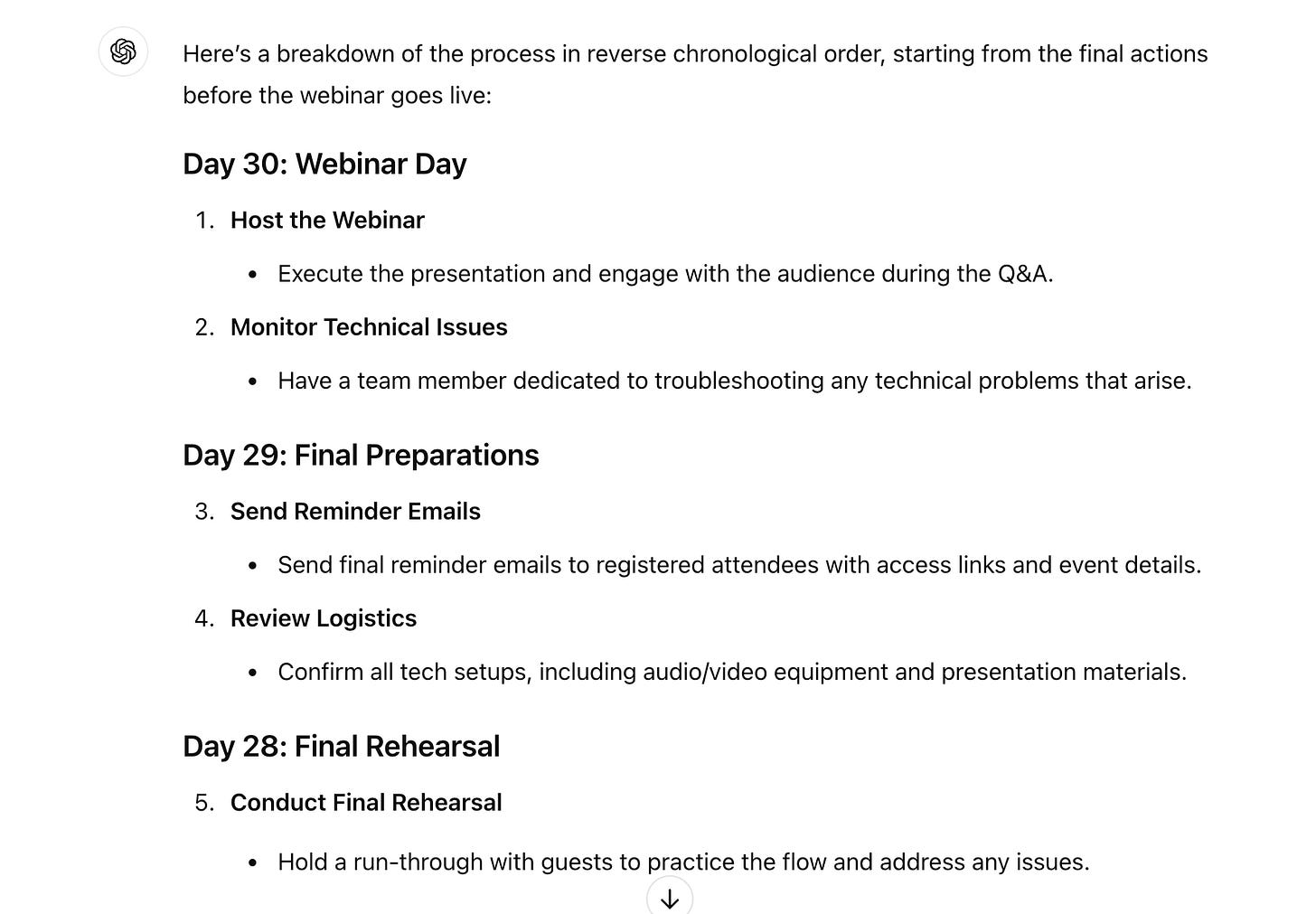

The first way to escape the planning fallacy is through backwards or reverse planning, where you plan in reverse chronological order from finish to start.

Example: you’re planning a webinar for next month. With traditional planning, you start by making a list of everything you need to get done between now and then:

Define the topic

Invite the speakers

Prepare the landing page and other marketing materials

Etc.

With backwards planning, you start from the opposite end. You consider the last actions you’ll need to take, like having the speakers online 15 mins earlier for a final check, and work backwards from there:

Send out the ‘1 hour to the event’ reminder email

Publish a final call for attendees on LinkedIn a few hours before

…and so on, until you’ve listed everything leading up to your deliverable and found yourself back at the start.

Why it works → apparently, the reverse planning approach leads to “greater motivation, higher goal expectancy, less time pressure, and better goal-relevant performance.”2 The theory is that backwards planning forces you to break usual thinking patterns and consider a project from an alternative perspective, which in turn helps build more realistic estimates and see potential obstacles you’d otherwise overlook.

💡 A practical example 💡

Back in September, we ran a live session at Float. As the project driver, I built a FigJam board with a rectangular block for each week that separated us from the session (the grey blocks you see below), then started working backwards.

I noted what needed to happen in the hour before going live, then the previous 24-48 hours, and kept working backwards until I had broken the project down into its main tasks in reverse order.

This is what it looked like:

When you see the board, you don’t notice any difference: the result looks the same as a traditional forward plan, so all stakeholders can read it from left to right as they normally would.

💡 pro tip: the whiteboard format works well for a top-level view, but I don’t recommend doing all your planning on it. Once I had these blocks, I broke each down into smaller tasks in a separate project management tool with specific assignees and due dates. By the end, there were 50+ tasks spread over 3 weeks.

Method two: use an AI co-pilot 🤖

The planning fallacy happens because of the human tendency to focus narrowly on a current project and ignore relevant info and data points about how similar ones have fared before.

But you know who/what has a lot of that data? Large Language Models. I hadn’t thought of this second method, using an AI co-pilot, until my teammate Stella mentioned it. For example, a simple ChatGPT prompt like this:

results in a thorough list of potential milestones and actions:

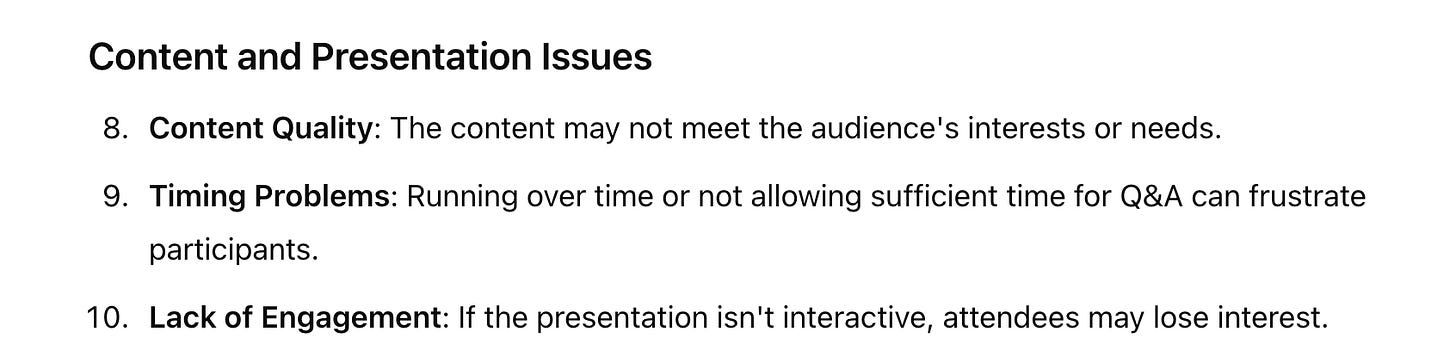

You can also ask the AI to list all the worst-case scenarios, which makes it easier to prepare buffers and contingency plans. If you were prompting for a live session, you’d get a list of 23 neatly categorised items, like:

or:

And yes, some seems rather obvious—but if you forget to think about them, you could end up in quite a lot of trouble. For example: timezone misalignment (#14) is such an easy thing to mess up. For our Float event, with a guest in Vancouver (where it was Tuesday afternoon) and one in Sydney (where it was already Wednesday morning), you better believe I checked calendar alignment about fifteen times just to make sure everybody would show up when and where they should.

💡 word of advice: don’t outsource your entire thinking process to AI tools, use them as co-pilots to sense-check your existing work. Make your (backwards) plan first, then give ChatGPT a relevant plan-focused prompt, so you can learn how to spot and fill gaps in your logic and timelines. Compare your list of what could hypothetically go wrong with an LLM list of what has definitely gone wrong before, so you can build and sharpen your prediction skill muscle.

Backwards planning is how I’ve been planning the vast majority of my work and projects for the last 10+ years—though young me from a decade ago didn’t imagine a future where I’d be doing it with an AI copilot. There’s never a dull moment in this world of marketing and tech, huh 😅 🤦♀️

Happy planning,

Here is the 1977 paper where Kahneman & Tversky introduced the concept of planning fallacy. I enjoyed reading some of it, but they lost me around page 37.

From this (paywalled) paper on the relative effects of forward and backward planning on goal pursuit.

Hi Fio,

Retro engineering is indeed a great tactic. I would add that sometimes, it can be the other way around: people think that your project needs only 4 hours of work when it needs above well above 6 hours.

Thank you for sharing this approach! I've also found it more effective than traditional planning.

You mentioned FigJam as a tool for high-level planning. I've noticed that people often compare Miro boards with FigJam, and I usually work with Miro. So, I was wondering why you prefer FigJam. Could you share your thoughts?